Ewer with a Bacchanal and the Triumph of the Sea Gods

France (Limoges)

Third quarter of the 16th century

Signed I.C., inscribed with the inv. no. G – R 772 in red ink on the underside

Grisaille and camaieu enamels

Height: 27 cm

Provenance

Collection of Maximilian von Goldschmidt – Rothschild, sold at auction at Parke-Bernet Galleries, New York, April 13, 1950;

The Ernest Brummer Collection: Auction sale, 16-19 October 1979, Zurich, Galerie Koller & Spink & Son (sale no. 257, cat pages 396-399);

Private American Collection.

This finely chased copperplate ewer with grisaille painting is an outstanding work of Limousin enamel produced in the 16th century. The signature ‘I.C.’ is incised on the inner surface of the double-walled spout.

As there are certain stylistic differences between the individual elements it is now assumed that the monogram ‘IC’ is not the signature of one particular artist but is the mark of a workshop. It probably refers to several enamellers with a similar or the same name who were active in the second half of the 16th century and later .

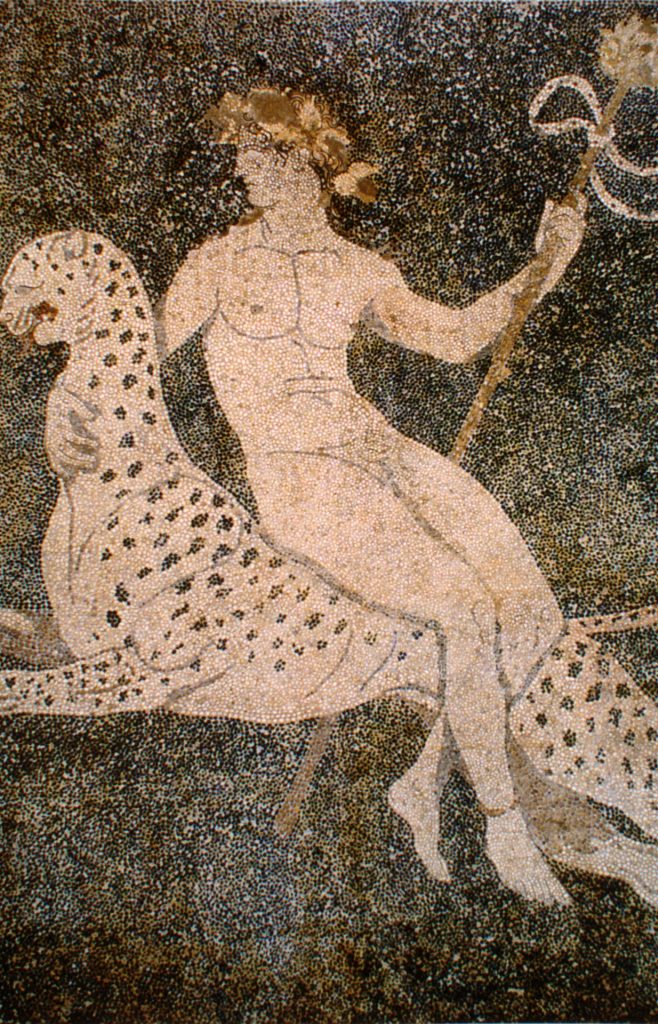

Thematically, an exuberant bacchanal dominates the ewer’s decoration. It was modelled on the engraving ‘The Triumph of Bacchus’ (c. 1546) by the French architect and draughtsman Jacques Androuet Ducerceau (before 1520–1585/86) that is one of a widespread series of designs for vessels. The composition, originally conceived as a decoration for a bowl or basin, has been transferred here to the main body of the ewer, albeit in a more compact style and with several modifications made by the enameller.

A boisterous celebration is depicted: Silenus, drunk and exhausted from all the revelry, is seated on a donkey and supported by two elderly satyrs; another is holding Silenus’ mantle, dynamically caught in motion, that is about to slip from his shoulder. Other satyrs are playing the syrinx and trumpet. A small child and a billy goat form a second group of mounted characters. Through the light colour of the skin the figures are decoratively set off against the dark enamel background that is brightened by bushes highlighted in white and gold.

The shoulder of the ewer is decorated with a number of frolicking aquatic creatures based on ‘The Triumph of Neptune and Amphitrite’, another work by Jacques Androuet Ducerceau. A group of mythical monsters is splashing around in a skillfully depicted foaming sea of white, wavy lines on a dark background. Winged stags, a bull ridden by a fabulous masked creature with wings, a female centaur, a woman with bats’ wings, a Triton, a Nereid and another mythical creature are dancing on the waves.

Enamel objects with decorative grisaille painting are typical of the ‘IC’ workshop. Figurative and decorative elements are applied in white on a dark ground with delicately differentiated areas of light and shade. Grisailles were left monochrome or, in this case, coloured by pigments applied on top, creating the illusion of a bas-relief.

Jacques Androuet Ducerceau, whose engravings provided the basis for the ornamentation on the ewer, strongly influenced Limousin decoration in the 16th century with his graphic designs. Stylistically these belong to the Fontainebleau School, a French variation of Mannerism. Thanks to printmaking, these popular artistic models soon became widespread.

Our ewer belongs to a large group of very similar vessels from the workshop of the monogrammist ‘IC’ that are characterised by the same decorative principle . At the time they were made, enamel objects of this quality were considered absolute luxury items, intended less for everyday use and more as decoration in a nobleman’s palace or a wealthy burgher’s house. Several enamellists from Limoges even created portraits for the French royal household.

Today, enamel objects bearing the signature ‘I.C.’ can be found in international museum collections including the Louvre, the Frick Collection and the Walters Art Museum.